This is an exciting time for someone who teaches about the legal representation of children in foster care. Florida is currently in the middle of the most public discussion of its system we have ever had, and I am loving it. There has been a full OPPAGA report, four senate committee hearings (including presentations by judges with differing viewpoints), op-eds calling for a change, and a senate bill proposing a new program to provide direct legal representation to older foster children. Whatever happens in the end, this discussion is healthy.

It’s also the culmination of a decade of pent up disagreement about the direction of the GAL Program and how it can best serve children. That shouldn’t have happened. The statute creating the Program requires the executive director to be appointed every three years after publicly advertising the position and publicly interviewing the candidates. Every three years we should have heard competing visions of the Program and a transparent discussion of where it should go next. Instead, a (legally debatable) loophole in the statutory language permitted two governors in a row to re-appoint the current director without that public process. That turned policy into politics. There were people both in and out of the Program who would have applied. Instead many of them are now gone. (Confession: I’m not one of them. Running a statewide agency is not in my wheelhouse.)

Part of having a meaningful debate about the future of child representation in Florida requires having a shared understanding of the existing system. The GAL Program has done a masterful marketing job of making the term “guardian ad litem” synonymous with volunteer advocacy. That is only part of what the Program actually does. This post looks at something I’ve never seen publicly detailed before: how the GAL Program spends its money.

What does a guardian ad litem do in Florida?

It’s helpful to start with a reminder of what a guardian ad litem does in Florida dependency cases. The statutes say that GALs are appointed “to represent the best interest of the child,” but the law doesn’t provide much guidance as to what that means in practice. According to the statutes, GALs in dependency cases must (1) review DCF’s dispositional recommendations and changes in placement, (2) file a dispositional report, and (3) be present at all critical stages of a case or file a written report. GALs also must be appointed to TPR cases and file written recommendations that include the child’s wishes. They also have similar obligations as other parties, such as participating face-to-face in case plan hearings and maintaining confidentiality.

It’s important to say what is not in the statutes creating the guardian ad litem. There is no requirement that the GAL be a volunteer, that the GAL be represented by an attorney, or that the GAL do any independent investigation or appear in court except in TPR cases. The statutes even give the GAL the option of filing a written report of findings and recommendations in most situations. In theory, the statutory duties could be performed by a handful of staff or volunteers in each circuit doing file reviews and a specialized TPR team. This would not be a particularly good system, but it would be a legal one.

The GAL Program is not required by the law to have its current structure. It’s the result of policy choices by its leadership over the last 17 years. Listening to the public discussion this year, it seems the GAL Program has defined itself in four different ways:

A volunteer mentorship program. In hearings and op-eds, supporters of the Program have repeatedly pointed to examples of GALs serving as mentors for kids. We hear about the hours that the volunteers spend with the children, the miles driven, and the money spent. Someone even rhetorically asked at a hearing, “If children get attorneys instead, who will take them to get their hair cut?” The answer should be their foster parents, but that’s a different discussion.

A fact investigation program. The GAL Program talks a lot about the factual information brought to the court through its volunteers. This was the traditional function and major innovation of CASA in the early days. Volunteers had the time to go out and interview everyone, and then the time to sit in court until it was their turn to report. Today we have a lot more investigatory resources and reports coming to the court through professionals, but the barriers to everyone in a child’s life participating in hearings are still there.

A fundraising program. The GAL Program raises and spends money on material items that foster kids need, mostly through its direct support organizations. This includes normalcy items like clothes for prom and services like tutoring or therapy that aren’t covered by other funding sources. I want to note that they don’t pay for all kids’ needs — just the kids who are represented by the Program. I have made requests and been told no until the court appoints them to one of my clients.

A legal advocacy program. The GAL Program has lawyers, advocates in court, and does legal trainings and pro bono recruitment. (Their legal training materials are really good.) The Program doesn’t typically highlight this work when doing public outreach. I’ve spoken to people involved in marketing and fundraising for the Program who acknowledge that donors don’t feel warm and fuzzy about paying for lawyers and paralegals the way they feel about paying for prom dresses. Court puppies and mentorship moments bring in more money than depositions, no matter how outcome determinative they may be. The Program typically only focuses on its legal advocacy work when it is swatting away calls for children in foster care to get attorneys.

At one committee hearing, a speaker supporting the current GAL Program said it has always had to choose between quantity and quality — between representing all children poorly or representing some children very well. That seemed so reasonable at the time he said it: another underfunded charitable organization just trying to survive. Except that the GAL Program is not a charitable organization: it’s a $50 million per year government agency. And its budget tells a much more complex story about the choices that its leadership has made.

What does the Guardian ad Litem Program spend money on?

The OPPAGA report had a statistic that raised a lot of eyebrows, even from people who are supportive of the GAL Program in general. Since 2016 it has received 14% more money but managed to represent 3,500 fewer children. The Program has given no real explanation for the reduction. That high-profile supporter suggested that this was an intentional choice by the Program so that it could focus on higher quality advocacy. The law says that every child must have an advocate.

The OPPAGA report describes the multidisciplinary team model that the GAL Program uses on cases. It consists of a volunteer or a staff guardian, a child advocate manager, and a lawyer. OPPAGA did not give any information on whether this model was being implemented efficiently. The OPPAGA report includes a chart of comparable systems in other states. Florida’s GAL Program had 3.7 times the state funding as the next largest state (which was Texas, and most of its funding came from other sources). North Carolina, the state with a multidisciplinary model similar to ours, spent $986 per child compared to Florida’s $1,600. I have no idea if one program is better than the other, but the Florida GAL Program was supposed to be the model of cost effectiveness. This suggests there are other options out there worth exploring. These are the types of things we should talk openly about.

To begin to answer these questions, we need to know how the GAL Program spends its money. That’s what this post is about. As a caveat, I want to say that I’m not an accountant or an expert in public administration. My best party trick is making public records requests and colorful charts from the results. I hope someone with the right expertise takes a look at this and continues the conversation.

Here’s a little about the methodology I’ve used. I’ve made choices about how to group expenditures into categories to make them more understandable. I’m also including the expenditures by the direct support organizations (like the Guardian ad Litem Foundation or Voices for Children) because they fundraise on the name of the Program and fund positions and expenses for the Program. If anyone disagrees with this methodology, the source documents are all publicly available. The data in this post comes from the following places:

- A public records request on the GAL Program’s expenditures by object code and category, for both general revenue and grants. I have this for fiscal years 2015-16 through 2019-20.

- A public records request on the GAL Program’s FTE positions. I have two versions of this. One shows the available positions at the end of each fiscal year from 2016 to 2020. The other shows the active employees on February 1, 2020.

- A review of the most recent available 990 tax forms for the direct support organizations that I could find. Some DSOs filed full 990s and others filed short forms, which limited the details available. I tried to use the same functional expenses categories for each, but I had to guess in some cases. The amount that I guessed on was less than 1% of the total budget.

- The Department of Financial Services catalog of State Financial Assistance Programs.

- Legislative appropriations.

- GAL Program reports.

Let’s begin.

The basics

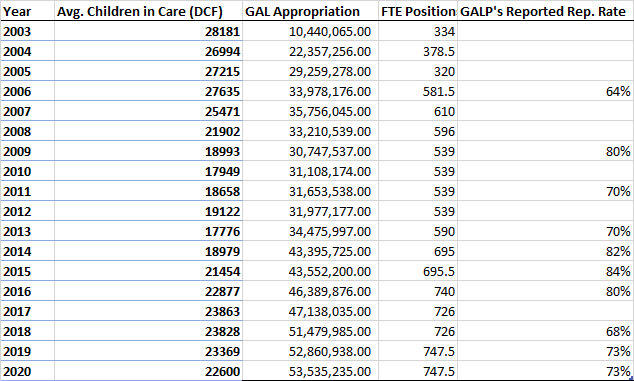

The GAL Program’s annual state appropriations have increased 512% since its creation. In 2003, it was appropriated $10.3 million. In 2020, the amount was $53.5 million. Budget negotiations for this year are not complete, but the House’s budget currently proposes $56.5 million and the Senate’s budget proposes $54.2 for the Program.

Over the same period of time, the number of positions at the GAL Program more than doubled from 320 at its lowest to 748 in 2020. As with any organization, not all positions are filled at any given time. The House’s budget this year proposes 759 FTEs, and the Senate’s budget proposes 723.

The GAL Program’s annual reports typically list a representation rate for that year. More recently the Program has issued performance reports. There’s no public repository of the historical reports, but some are available online. I’m not plotting this data because I have no way of saying how these rates were calculated or whether they used a consistent methodology year to year. The Program claims to have hit a rate of 84% in 2015, at the beginning of the latest expansion, and a recent low of 68% at the height of that expansion. OPPAGA put the rate at around 67%, which is why knowing the methodology is important.

The final group of expenditures is money raised by the Direct Support Organizations and grants received by the Program. The OPPAGA report shows that those funds have increased a lot over the last few years.

A word of caution about the DSOs, however. They raise money for the local programs, and Voices for Children in Miami is the bulk of that money. Voices for Children also receives over $900,000 in state financial assistance from the legislature to augment salaries the organization is paying at the Miami office. The DSO money is therefore not 100% donations.

So, increases across the board but lower representation rates. Where does the money go?

The expenditures

The next chart is the meat of this post. This is an approximation of the GAL Program’s expenditures for 2019-20 based on the records described above. I’ve added 30% to the salaries to account for benefits, which have been removed from the expenses group. OPS employees were converted to an FTE without benefits. I created six categories and tried to consolidate the expense codes as much as possible.

The chart accounts for approximately $53.8 million in GAL Program and DSO spending. About 62% of this pays for that three-person multidisciplinary team: 35% for recruitment, training, and management of volunteers; 21% for attorneys and legal costs; and 6% towards unknown salaries paid for by the DSOs, which I’ll assume go to front-line staff. The rest of the expenditures are local and statewide managerial positions, administrative support, normal organizational expenses like photocopying and insurance, and state financial grants to support two local programs: the Orange County program and Voices for Children in Miami.

What stands out to me is that the GAL Program could probably hit 100% representation if it would pick one thing and stick to it. I said I’m not a public administration expert, but the budgeting choices here seem fairly straightforward. The Program could be a traditional CASA program with money to spare by redirecting the legal staff, top-heavy managerial structure, and some of the administrative positions into recruitment and CAM positions. It could be a pretty large law firm with a more-manageable caseload if it redirected the CASA-model elements into attorneys and investigators (the GAL program attorneys currently handle 100+ cases, which is not good) and streamlined the managerial structure. Or maybe that high-profile supporter of the Program is correct and this is the necessary but imperfect balance of all the faces of the GAL Program. Could it be done better? I’m sure someone with more expertise than me could say. All I know is there is no lack of money to work with here.

Nobody is making a fortune either. Here is the state salary distribution. Bosses and lawyers get paid the most, with case management staff and then administrative staff making the least.

And finally here are the top 10 salaries in GAL-world. The highest paid employees are at Voices for Children in Miami, which also had the highest DSO expenditures and over $2 million in assets, so maybe this is defensible. Only two state employees make six figures, and only seven make more than $75,000.

| Name | Title | Annual Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Nelson Hincapie | CEO of Voices for Children (Miami) | $ 237,747 |

| Tania Rodriguez | COO of Voices for Children (Miami) | $ 169,914 |

| Alan Abramowitz | Executive Director | $ 127,954 |

| Dennis Moore | General Counsel | $ 116,911 |

| Kristen Solomon | Director of Operations | $ 98,417 |

| Debra Ervin | Administrative Services Director | $ 90,413 |

| Gregory Ramsey | Chief Information Officer | $ 89,673 |

| Thomasina Moore | General Counsel | $ 88,359 |

| Amy Foster | ED at GAL Foundation Tampa Bay | $ 77,962 |

| Laurie Blades | Regional Director | $ 77,250 |

| David Windle | Finance and Budget Director | $ 74,624 |

Most of the other 709 employees are paid significantly less. When I left the GAL Program in 2011 as a Senior Program Attorney I think I made around $47,000.

In the next sections, let’s take each of the groups above and look at them in more detail. We begin with the core of the CASA model.

Case Management

Since 2015, the GAL Program has spent approximately $66 million on case management. I’m including in this group the recruitment, training, and supervision of the volunteers. This also includes the CAMs who function as staff advocates and have their own case loads. The Program’s pay plan lists CAMs as either doing the job responsibilities directly or through volunteers.

Every CAM does the job differently, but the main function for those working with volunteers is to keep them on task. A CAM can spend significant time on the phone reminding volunteers about visits, upcoming court dates, and deadlines to submit drafts of reports. They spend time explaining administrative process (e.g., how home studies work) and investigation strategy (e.g., talk to the school counselor not just the principal). The CAMs typically edit the GAL reports submitted by volunteers or write them from scratch for volunteers who cannot or will not do the draft. CAMs go to court or participate in staffings sometimes, especially on contentious cases where the volunteer needs support. At the local level, the CAMs are supervised by the CAM IIs, Program Directors, and Circuit Directors.

About $5.5 million was spent on volunteer recruitment staff since 2015. Some of these staff are hired as OPS. Recruiters hold events in the community, field questions, and coordinate trainings. Turnover in volunteers is a constant for any organization that relies on them. The GAL Program advocacy snapshot for November 2020 showed that about 65% of certified volunteers were active. Coincidentally, that is the same percentage of children the Program represents — another opportunity to reach 100%.

Over time, expenditures on case management have gone up in large part due to a budget increase in 2017-18.

Despite the pay increase, FTEs for case management went down through 2018-19 and rebounded slightly in 2019-20.

Finally, looking only at 2019-20, the CAMs were largely hired in the last five years with a sizeable spike in the last two years. The CAM IIs follow a similar pattern, but there are a number of this group that has been with the Program since it was created in 2004. There are two employees in this group who have been with the Program since its time as a court program.

Lastly, pay for CAMs does increase with time, but really only for those who have been there 10+ years. The newer employees seem to have very flat pay tracks. Those two CAMs making close to $50k are in the 16th Circuit.

Legal Advocacy

Unlike the CAMs and CAM IIs, legal salaries are reversed. Most of the Program Attorneys are classified as “senior,” which comes with a pay bump. Legal expenses are a small portion of the budget, and only a few circuits have designated legal secretaries. In other circuits, administrative staff help with record pulls and filings.

The same decrease in FTEs is seen in the lawyers in 2018-19, before rebounding in 2019-20.

And there was a similar decrease in expenditures. It seems notable that litigation expenses decreased, too. Either those costs got picked up by a DSO or this reflects an intentional shift away from legal advocacy. I’d love to hear more about what happened there.

Most program attorneys were hired in the last few years, but there are some that have been with the Program since its creation. Senior Program Attorney status seems to be based on tenure, but there are two attorneys who may want to ask some questions.

Attorneys also see slightly higher pay over time, but again only if you’re in the right circuits. The rest are one two tracks: Attorney and Senior Attorney, with a few statewide lawyers handling appeals coming in higher.

Administrative Staff

The Program has spent about $24.5 million on administrative costs over the last 5 years. This group is actually three: statewide administrative staff like financial officers or information technology directors, local administrative staff like secretaries and assistants, and all the miscellaneous expenses that every organization has, like copy paper and maintenance. I’ve chosen to lump them together because all of these expenses provide support to the core mission of the Program without providing managerial or front-line services. The bulk of this group is the salary for local administrative staff.

The administrative FTEs saw a drop in 2017-18, mostly at the local level.

There was also a dip in expenditures in this group.

Most administrative staff were hired in the past few years, but some have been with the Program since its creation.

The local administrative salaries show less stratification. The range from from $25k to $40k is not huge, but at least there’s hope of a raise over time.

Managerial Staff

The Program has spent about $23 million on managerial staff since 2015. The Program has a lot of bosses. On the case management side, there are local program directors, local circuit directors, regional directors, and statewide program directors. The legal side is a bit thinner with managing attorneys in each circuit, regional legal counsels, and two statewide general counsels.

Interestingly, there wasn’t a decrease in managerial staff in 2018-19 like we saw in case management and legal.

And there was only a slight decrease in expenditures on management over that time.

Finally, the date of hire for the managerial staff is significantly different than front line and administrative staff. The management, especially the circuit directors, have been around a lot longer — many since the beginning and about half since before the hire of the current Executive Director in 2010. I’ve added labels for the circuit numbers just to show the distribution.

Everything over Time

When you put that all together, you can see the efforts of the Program over time. It did expand expenditures on case management and legal. It managed to keep most other categories constant. Yet it still represented 3,500 fewer children.

However, not every circuit saw the same increases over those years. The largest increase was in Circuit 7 (Flagler, Putnam, St. Johns, Volusia), and neighboring Circuit 18 (Brevard, Seminole). Some circuits came out pretty even. Circuit 16 (Monroe) was the only circuit to lose state funding during this process.

Here are the changes by each group. The changes were largely seen in case management and legal.

Conclusion

Nothing in these numbers explains why the GAL Program represented 3,500 fewer children over the last four years. The existential question for the Program’s leadership going forward is whether they can actually accomplish the goal of 100% representation. Throwing money at it doesn’t seem to be working. It may be time to try something new.

Leave a Reply